.jpg?bossToken=cd550b2fd8bf8868602c6adb0f9815e77d7c15d9f32b1e292f79161b92921b1b)

Photo Attribution: John Michael Wright, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

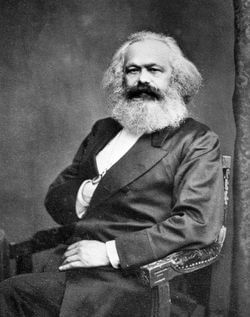

Thomas Hobbes

This example has been viewed 226x times

Summary

Rodden Rating

Analysis for Thomas Hobbes

Biography

Thomas Hobbes (/hɒbz/ HOBZ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory.[4] He is considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy.[5][6]

In his early life, overshadowed by his father's departure following a fight, he was taken under the care of his wealthy uncle. Hobbes's academic journey began in Westport, leading him to the University of Oxford, where he was exposed to classical literature and mathematics. He then graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1608. He became a tutor to the Cavendish family, which connected him to intellectual circles and initiated his extensive travels across Europe. These experiences, including meetings with figures like Galileo, shaped his intellectual development.

After returning to England from France in 1637, Hobbes witnessed the destruction and brutality of the English Civil War from 1642 to 1651 between Parliamentarians and Royalists, which heavily influenced his advocacy for governance by an absolute sovereign in Leviathan, as the solution to human conflict and societal breakdown. Aside from social contract theory, Leviathan also popularized ideas such as the state of nature ("war of all against all") and laws of nature. His other major works include the trilogy De Cive (1642), De Corpore (1655), and De Homine (1658) as well as the posthumous work Behemoth (1681).

Hobbes contributed to a diverse array of fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, optics, theology, classical translations, ethics, as well as philosophy in general, marking him as a polymath. Despite controversies and challenges, including accusations of atheism and contentious debates with contemporaries, Hobbes's work profoundly influenced the understanding of political structure and human nature.

Biography Early life Thomas Hobbes was born on 5 April 1588 (Old Style), in Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. Having been born prematurely when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, Hobbes later reported that "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear."[7] Hobbes had a brother, Edmund, about two years older, as well as a sister, Anne.

Although Thomas Hobbes's childhood is unknown to a large extent, as is his mother's name,[8] it is known that Hobbes's father, Thomas Sr., was the vicar of both Charlton and Westport. Hobbes's father was uneducated, according to John Aubrey, Hobbes's biographer, and he "disesteemed learning."[9] Thomas Sr. was involved in a fight with the local clergy outside his church, forcing him to leave London. As a result, the family was left in the care of Thomas Sr.'s older brother, Francis, a wealthy glove manufacturer with no family of his own.

Education Hobbes was educated at Westport church from age four, went to the Malmesbury school, and then to a private school kept by a young man named Robert Latimer, a graduate of the University of Oxford.[10] Hobbes was a good pupil, and between 1601 and 1602 he went to Magdalen Hall, the predecessor to Hertford College, Oxford, where he was taught scholastic logic and mathematics.[11][12][13] The principal, John Wilkinson, was a Puritan and had some influence on Hobbes. Before going up to Oxford, Hobbes translated Euripides' Medea from Greek into Latin verse.[9]

At university, Thomas Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum as he was little attracted by the scholastic learning.[10] Leaving Oxford, Hobbes completed his B.A. degree by incorporation at St John's College, Cambridge, in 1608.[14] He was recommended by Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, as tutor to William, the son of William Cavendish,[10] Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl of Devonshire), and began a lifelong connection with that family.[15] William Cavendish was elevated to the peerage on his father's death in 1626, holding it for two years before his death in 1628. His son, also William, likewise became the 3rd Earl of Devonshire. Hobbes served as a tutor and secretary to both men. The 1st Earl's younger brother, Charles Cavendish, had two sons who were patrons of Hobbes. The elder son, William Cavendish, later 1st Duke of Newcastle, was a leading supporter of Charles I during the Civil War in which he personally financed an army for the king, having been governor to the Prince of Wales, Charles James, Duke of Cornwall. It was to this William Cavendish that Hobbes dedicated his Elements of Law.[9]

Hobbes became a companion to the younger William Cavendish and they both took part in a grand tour of Europe between 1610 and 1615. Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during the tour, in contrast to the scholastic philosophy that he had learned in Oxford. In Venice, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, an associate of Paolo Sarpi, a Venetian scholar and statesman.[9]

His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at a careful study of classical Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of which was, in 1628, his edition of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War,[10] the first translation of that work into English directly from a Greek manuscript. Hobbes professed a deep admiration for Thucydides, praising him as "the most politic historiographer that ever writ," and one scholar has suggested that "Hobbes' reading of Thucydides confirmed, or perhaps crystallized, the broad outlines and many of the details of [Hobbes'] own thought."[16] It has been argued that three of the discourses in the 1620 publication known as Horae Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses also represent the work of Hobbes from this period.[17]

Although he did associate with literary figures like Ben Jonson and briefly worked as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, translating several of his Essays into Latin,[9] he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629. In June 1628, his employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague, and his widow, the countess Christian, dismissed Hobbes.[18][19]

In Paris (1629–1637) Hobbes soon (in 1629) found work as a tutor to Gervase Clifton, the son of Sir Gervase Clifton, 1st Baronet, and continued in this role until November 1630.[20] He spent most of this time in Paris. Thereafter, he again found work with the Cavendish family, tutoring William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, the eldest son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven years, as well as tutoring, he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy, awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Galileo Galilei in Florence while he was under house arrest upon condemnation, in 1636, and was later a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.[18]

Hobbes's first area of study was an interest in the physical doctrine of motion and physical momentum. Despite his interest in this phenomenon, he disdained experimental work as in physics. He went on to conceive the system of thought to the elaboration of which he would devote his life. His scheme was first to work out, in a separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion, at least as motion or mechanical action was then understood. He then singled out Man from the realm of Nature and plants. Then, in another treatise, he showed what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions whereby Man came into relation with Man. Finally, he considered, in his crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued how this must be regulated if people were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery". Thus he proposed to unite the separate phenomena of Body, Man, and the State.[18]

In England (1637–1641) Hobbes came back home from Paris, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent, which disrupted him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan.[18] However, by the end of the Short Parliament in 1640, he had written a short treatise called The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic. It was not published and only circulated as a manuscript among his acquaintances. A pirated version, however, was published about ten years later. Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the sitting of the Short Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly mark the influences of the rising political crisis. Nevertheless, many (though not all) elements of Hobbes's political thought were unchanged between The Elements of Law and Leviathan, which demonstrates that the events of the English Civil War had little effect on his contractarian methodology. However, the arguments in Leviathan were modified from The Elements of Law when it came to the necessity of consent in creating political obligation: Hobbes wrote in The Elements of Law that patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were. This was perhaps a reflection either of Hobbes's thoughts about the engagement controversy or of his reaction to treatises published by Patriarchalists, such as Sir Robert Filmer, between 1640 and 1651.[citation needed]

When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was in disfavour due to the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris. He did not return for 11 years. In Paris, he rejoined the coterie around Mersenne and wrote a critique of the Meditations on First Philosophy of René Descartes, which was printed as third among the sets of "Objections" appended, with "Replies" from Descartes, in 1641. A different set of remarks on other works by Descartes succeeded only in ending all correspondence between the two.[21]

Hobbes also extended his own works in a way, working on the third section, De Cive, which was finished in November 1641. Although it was initially only circulated privately, it was well received, and included lines of argumentation that were repeated a decade later in Leviathan. He then returned to hard work on the first two sections of his work and published little except a short treatise on optics (Tractatus opticus), included in the collection of scientific tracts published by Mersenne as Cogitata physico-mathematica in 1644. He built a good reputation in philosophic circles and in 1645 was chosen with Descartes, Gilles de Roberval and others to referee the controversy between John Pell and Longomontanus over the problem of squaring the circle.[21]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hobbes

**** DISCLAIMER: Gregorian birthdate of Thomas Hobbes is April 15th 1588 which is casted here, and for time of birth, we used the rectified time courtesy of Astrotheme (https://www.astrotheme.com/astrology/Thomas_Hobbes). Please use your own discernment re accuracy of the symbol/degree of the moon & the Glyph. Gaia

Raw Data

Horoscope Data

Comments

Natal Data

1588-04-15 05:08:00 GMT

51° 35′ 10.9″ N 2° 6′ 10.2″ W

Malmesbury SN16, UK

.jpg?bossToken=08c481a3fa0c716226f91b7380858b2bc4263bf36df763df30dfc804d5be6135)

.jpg?bossToken=9d0bc5a6e5284506e0471a0fa91f6fbdb63658cdc38db0091f052944939a8e6f)

.jpg?bossToken=75a7784a120ba10468d4cd319e4be33e118820d515a27c248600a828d1251010)