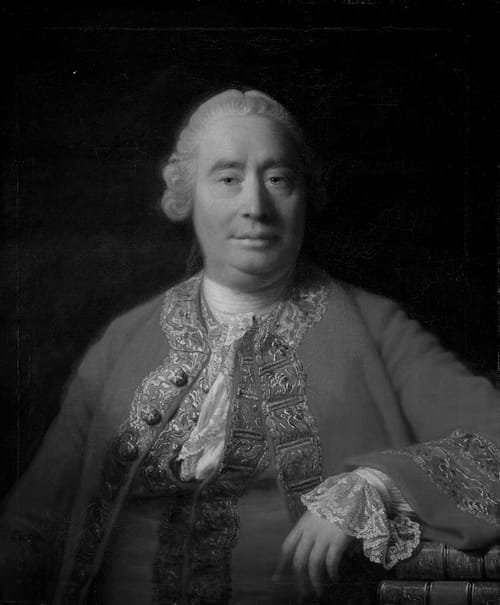

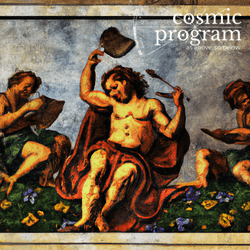

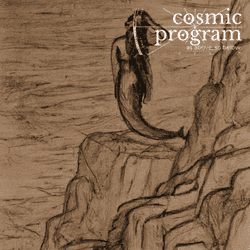

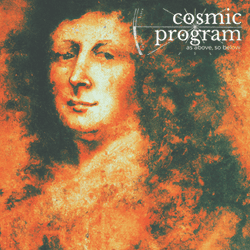

Photo Attribution: Allan Ramsay, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

David Hume

This example has been viewed 222x times

Summary

Rodden Rating

Analysis for David Hume

Biography

David Hume (/hjuːm/; born David Home; 7 May 1711 – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism.[1] Beginning with A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40), Hume strove to create a naturalistic science of man that examined the psychological basis of human nature. Hume followed John Locke in rejecting the existence of innate ideas, concluding that all human knowledge derives solely from experience. This places him with Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and George Berkeley as an empiricist.[7][8][9]

Hume argued that inductive reasoning and belief in causality cannot be justified rationally; instead, they result from custom and mental habit. We never actually perceive that one event causes another but only experience the "constant conjunction" of events. This problem of induction means that to draw any causal inferences from past experience, it is necessary to presuppose that the future will resemble the past; this metaphysical presupposition cannot itself be grounded in prior experience.[10]

An opponent of philosophical rationalists, Hume held that passions rather than reason govern human behaviour, famously proclaiming that "Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions."[7][11] Hume was also a sentimentalist who held that ethics are based on emotion or sentiment rather than abstract moral principle. He maintained an early commitment to naturalistic explanations of moral phenomena and is usually accepted by historians of European philosophy to have first clearly expounded the is–ought problem, or the idea that a statement of fact alone can never give rise to a normative conclusion of what ought to be done.[12]

Hume denied that humans have an actual conception of the self, positing that we experience only a bundle of sensations, and that the self is nothing more than this bundle of perceptions connected by an association of ideas. Hume's compatibilist theory of free will takes causal determinism as fully compatible with human freedom.[13] His philosophy of religion, including his rejection of miracles, and critique of the argument from design for God's existence, were especially controversial for their time. Hume left a legacy that affected utilitarianism, logical positivism, the philosophy of science, early analytic philosophy, cognitive science, theology, and many other fields and thinkers. Immanuel Kant credited Hume as the inspiration that had awakened him from his "dogmatic slumbers."

Early life Hume was born on 26 April 1711, as David Home, in a tenement on the north side of Edinburgh's Lawnmarket. He was the second of two sons born to Catherine Home (née Falconer), daughter of Sir David Falconer of Newton, Midlothian and his wife Mary Falconer (née Norvell),[14] and Joseph Home of Chirnside in the County of Berwick, an advocate of Ninewells. Joseph died just after David's second birthday. Catherine, who never remarried, raised the two brothers and their sister on her own.[15]

Hume changed his family name's spelling in 1734, as the surname 'Home' (pronounced as 'Hume') was not well-known in England. Hume never married and lived partly at his Chirnside family home in Berwickshire, which had belonged to the family since the 16th century. His finances as a young man were very "slender", as his family was not rich; as a younger son he had little patrimony to live on.[16]

Hume attended the University of Edinburgh at an unusually early age—either 12 or possibly as young as 10—at a time when 14 was the typical age. Initially, Hume considered a career in law, because of his family. However, in his words, he came to have:[16]

...an insurmountable aversion to everything but the pursuits of Philosophy and general Learning; and while [my family] fanceyed I was poring over Voet and Vinnius, Cicero and Virgil were the Authors which I was secretly devouring.

He had little respect for the professors of his time, telling a friend in 1735 that "there is nothing to be learnt from a Professor, which is not to be met with in Books".[17] He did not graduate.[18]

"Disease of the learned" At around age 18, Hume made a philosophical discovery that opened up to him "a new Scene of Thought", inspiring him "to throw up every other Pleasure or Business to apply entirely to it".[19] As he did not recount what this scene exactly was, commentators have offered a variety of speculations.[20] One prominent interpretation among contemporary Humean scholarship is that this new "scene of thought" was Hume's realisation that Francis Hutcheson's theory of moral sense could be applied to the understanding of morality as well.

From this inspiration, Hume set out to spend a minimum of 10 years reading and writing. He soon came to the verge of a mental breakdown, first starting with a coldness—which he attributed to a "Laziness of Temper"—that lasted about nine months. Scurvy spots later broke out on his fingers, persuading Hume's physician to diagnose him with the "Disease of the Learned".[21][22]

Hume wrote that he "went under a Course of Bitters and Anti-Hysteric Pills", taken along with a pint of claret every day. He also decided to have a more active life to better continue his learning.[23] His health improved somewhat, but in 1731, he was afflicted with a ravenous appetite and palpitations. After eating well for a time, he went from being "tall, lean and raw-bon'd" to being "sturdy, robust [and] healthful-like."[24][25][26] Indeed, Hume would become well known for being obese and having a fondness for good port and cheese, often using them as philosophical metaphors for his conjectures.[27]

Career Despite having noble ancestry, Hume had no source of income and no learned profession by age 25. As was common at his time, he became a merchant's assistant, despite having to leave his native Scotland. He travelled via Bristol to La Flèche in Anjou, France. There he had frequent discourse with the Jesuits of the College of La Flèche.[28]

Hume was derailed in his attempts to start a university career by protests over his alleged "atheism",[29][30] also lamenting that his literary debut, A Treatise of Human Nature, "fell dead-born from the press."[14] However, he found literary success in his lifetime as an essayist, and a career as a librarian at the University of Edinburgh. These successes provided him much needed income at the time. His tenure there, and the access to research materials it provided, resulted in Hume's writing the massive six-volume The History of England, which became a bestseller and the definitive history of England. For over 60 years, Hume was the dominant interpreter of English history.[31]: 120 He described his "love for literary fame" as his "ruling passion"[14] and judged his two late works, the so-called "first" and "second" enquiries, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding and An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, as his greatest literary and philosophical achievements.[14] He would ask of his contemporaries to judge him on the merits of the later texts alone, rather than on the more radical formulations of his early, youthful work, dismissing his philosophical debut as juvenilia: "A work which the Author had projected before he left College."[32] Despite Hume's protestations, a consensus exists today that his most important arguments and philosophically distinctive doctrines are found in the original form they take in the Treatise. Though he was only 23 years old when starting this work, it is now regarded as one of the most important in the history of Western philosophy.[12]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hume

Raw Data

Horoscope Data

Comments

Natal Data

1711-05-07 Unknown Time LMT

55° 57′ 11.7″ N 3° 11′ 17.8″ W

Edinburgh, UK

.png?bossToken=9cbc2242287a9d8db8cc0cd1844f71a0778e75a848c7e3293c144d4497278e2e)

.jpg?bossToken=49322f64b79ba87d6472c753d43da97b5f3a253b2af4821d18b22eef61c7cec6)

.jpg?bossToken=e54db2df310ca9c7cf7bf93c6265a0914ac167aab14e6c8a0b9b27d4c1db1c42)