.jpg?bossToken=ad06cb2b3e2d8e55b35082b8e431d51620649d75ac78db6419a6cc90d7227d78)

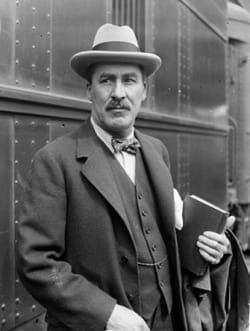

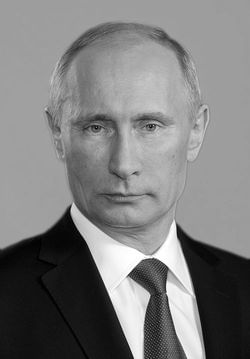

Photo Attribution: Ernst Milster, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Karl Richard Lepsius

This example has been viewed 552x times

Summary

Rodden Rating

Analysis for Karl Richard Lepsius

Biography

Karl Richard Lepsius (Latin: Carolus Richardius Lepsius) (23 December 1810 – 10 July 1884) was a Prussian Egyptologist, linguist and modern archaeologist.[1] He is widely known for his opus magnum Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien.

Early life

Karl Richard Lepsius was the son of Karl Peter Lepsius, a classical scholar from Naumburg, and his wife Friederike (née Gläser), who was the daughter of composer Carl Ludwig Traugott Gläser.[2] The family name was originally "Leps" and had been Latinized to "Lepsius" by Karl's paternal great-grandfather Peter Christoph Lepsius.[3] He was born in Naumburg on the Saale, Saxony.[4]

He studied Greek and Roman archaeology at the University of Leipzig (1829–1830), the University of Göttingen (1830–1832), and the Frederick William University of Berlin (1832–1833). After receiving his doctorate following his dissertation De tabulis Eugubinis in 1833, he travelled to Paris, where he attended lectures by the French classicist Jean Letronne, an early disciple of Jean-François Champollion and his work on the decipherment of the Egyptian language, visited Egyptian collections all over Europe and studied lithography and engraving.

Work

After the death of Champollion, Lepsius made a systematic study of the French scholar's Grammaire égyptienne, which had been published posthumously in 1836 but had yet to be widely accepted. In that year, Lepsius travelled to Tuscany to meet with Ippolito Rosellini, who had led a joint expedition to Egypt with Champollion in 1828–1829. In a series of letters to Rosellini, Lepsius expanded on Champollion's explanation of the use of phonetic signs in hieroglyphic writing, emphasizing (contra Champollion) that vowels were not written.

Denkmäler

Main article: Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien In 1842, Lepsius was commissioned (at the recommendation of the minister of instruction, Johann Eichhorn, and the scientists Alexander von Humboldt and Christian Charles Josias Bunsen) by King Frederich Wilhelm IV of Prussia to lead an expedition to Egypt and the Sudan to explore and record the remains of the ancient Egyptian civilization. The Prussian expedition was modelled after the earlier Napoleonic mission, with surveyors, draftsmen, and other specialists.[5] The mission reached Giza in November 1842 and spent six months making some of the first scientific studies of the pyramids of Giza, Abusir, Saqqara, and Dahshur. They discovered 67 pyramids recorded in the pioneering Lepsius list of pyramids and more than 130 tombs of noblemen in the area.[5] While at the Great Pyramid of Giza, Lepsius inscribed a graffito written in Egyptian hieroglyphs that honours Friedrich Wilhelm IV above the pyramid's original entrance; it is still visible.[6]

Working south, stopping for extended periods at important Middle Egyptian sites, such as Beni Hasan and Dayr al-Barsha. In 1843, he visited sites in Nubia such as Jebel Barkal, Meroë and Naqa, ruined ancient cities of the Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë, and copied some of the inscriptions and representations of the temples and pyramids there.[7]

Lepsius reached as far south as Khartoum, and then travelled up the Blue Nile to the region about Sennar,[citation needed] where he met members of the former Sudanese royal family, such as Nasra bint 'Adlan.[8] After exploring various sites in Upper and Lower Nubia, the expedition worked back north, reaching Thebes on November 2, 1844, where they spent four months studying the western bank of the Nile (such as the Ramesseum, Medinet Habu, the Valley of the Kings, etc.) and another three on the east bank at the temples of Karnak and Luxor, attempting to record as much as possible. Afterwards they stopped at Coptos, the Sinai, and sites in the Egyptian Delta, such as Tanis, before returning to Europe in 1846.[citation needed]

In 1845, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[9]

The chief result of this expedition was the publication of Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien (Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia), a massive twelve volume compendium of nearly 900 plates of ancient Egyptian inscriptions, monuments and landscapes, as well as accompanying commentary and descriptions. These plans, maps, and drawings of temple and tomb walls remained the chief source of information for Western scholars well into the 20th century, and are useful even today as they are often the sole record of monuments that have since been destroyed or reburied.[10] For example, he described a "Headless Pyramid" that was subsequently lost until May 2008, when a team led by Zahi Hawass removed a 25-foot-high sand dune to re-discover the superstructure (base) of a pyramid believed to belong to King Menkauhor.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Richard_Lepsius

Raw Data

Horoscope Data

Comments

Natal Data

1810-12-23 20:20:00 GMT

51° 9′ 7.3″ N 11° 48′ 51.3″ E

06 Naumburg, Germany

_03.jpg?bossToken=3b96efd5dc678c2731170fae8477af24d2f0e98104e3e5a80d47b6df0122e5b1)