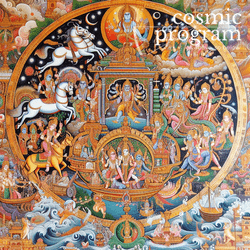

-850AD_(1).png?bossToken=5a609c9e9fc8df64097c3933d4d27ad8b9a43571ea3ab4c77750cf3502f0d10e)

Photo Attribution: Qanbar ‘Alî Naqqâsh Shirâzî, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Abu Ma‘shar (Albumasar)

This example has been viewed 394x times

Summary

Rodden Rating

Analysis for Abu Ma‘shar (Albumasar)

Biography

Abu Ma‘shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar (also Albusar, Albuxar, Albumazar; full name Abū Maʿshar Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Balkhī ابومَعْشَر جعفر بن محمد بن عمر بلخی; 10 August 787 – 9 March 886, AH 171–272),[3] was an early Persian[4][5][6] Muslim astrologer, thought to be the greatest astrologer of the Abbasid court in Baghdad.[1] While he was not a major innovator, his practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium.[3]

Life Abū Maʿshar was a native of Balkh, a town in the Balkh province of Afghanistan, approximately 74 kilometres (46 mi) to the south of the Amu Darya, one of the main bases of support of the Abbasid revolt in the early 8th century. Its population, as was generally the case in the frontier areas of the Arab conquest of Persia, remained culturally dedicated to its Sassanian and Hellenistic heritage. He probably came to Baghdad in the early years of the caliphate of al-Maʾmūn (r. 813–833). According to al-Nadim's Al-Fihrist (10th century), he lived on the West Side of Baghdad, near Bab Khurasan, the northeast gate of the original city on the west Bank of the Tigris.[7]

Abū Maʿshar was a member of the third generation (after the Arab Conquest) of the Pahlavi-oriented Khurasani intellectual elite, and he defended an approach of a “most astonishing and inconsistent” eclecticism. His reputation saved him from religious persecution, although there is a report of one incident where he was whipped for his practice of astrology under the caliphate of al-Musta'in (r. 862–866). He was a scholar of hadith, and according to biographical tradition, he only turned to astrology at the age of forty-seven (832/3). He became involved in a bitter dispute with al-Kindi (c. 796–873), the foremost Arab philosopher of his time, who was versed in Aristotelism and Neoplatonism. It was his confrontation with al-Kindi that convinced Abū Maʿshar of the need to study “mathematics” in order to understand philosophical arguments.[8]

His foretelling of an event that subsequently occurred earned him a lashing ordered by the displeased Caliph al-Musta'in. "I hit the mark and I was severely punished."[9]

Al-Nadim includes an extract from Abū Maʿshar's book on the variations of astronomical tables, which describes how the Persian kings gathered the best writing materials in the world to preserve their books on the sciences and deposited them in the Sarwayh fortress in the city of Jayy in Isfahan. The depository continued to exist at the time al-Nadim wrote in the 10th century.[10]

Amir Khusrav mentions that Abū Maʿshar came to Benaras (Varanasi) and studied astronomy there for ten years.[11]

Abū Maʿshar is said to have died at the age of 98 (but a centenarian according to the Islamic year count) in Wāsiṭ in eastern Iraq, during the last two nights of Ramadan of AH 272 (9 March 866). Abū Maʿshar was a Persian nationalist, studying Sassanid-era astrology in his "Kitab al-Qeranat" to predict the imminent collapse of Arab rule and the restoration of Iranian rule.[12]

Works Science of astrology His work Kitāb al-madkhal al-kabīr (English: The Great Introduction to the Science of Astrology) provides an introduction to astrology which received many translations to Latin and Greek starting from the 11th-century.[1]

In one part of this book he records the rising of tides in relation with the position of the Moon, noticing that there are two high-tides in a day.[13] He rejected Greek thought that moonlight influenced the tides and considered that the Moon had some astrological virtue that attracted the sea. These ideas were discussed by European medieval scholars.[14] It had significant influence on European medieval scholars, like Albert the Great who developed his own theory of tides based on a mix of both light and Abu Ma'shar virtue.[14]

Other work His works on astronomy are not extant, but information can still be gleaned from summaries found in the works of later astronomers or from his astrology works.[1]

Kitāb mukhtaṣar al-madkhal, an abridged version of the above, later translated to Latin by Adelard of Bath.[1] Kitāb al-milal wa-ʾl-duwal ("Book on religions and dynasties"), probably his most important work, commented on in the major works of Roger Bacon, Pierre d'Ailly, and Pico della Mirandola.[1] Fī dhikr ma tadullu ʿalayhi al-ashkhāṣ al-ʿulwiyya ("On the indications of the celestial objects"), Kitāb al-dalālāt ʿalā al-ittiṣālāt wa-qirānāt al-kawākib ("Book of the indications of the planetary conjunctions"), Kitāb al-ulūf ("Book of thousands"), preserved only in summaries by Sijzī.[1] Kitāb taḥāwīl sinī al-ʿālam (Flowers of Abu Ma'shar), uses horoscopes to examine months and days of the year. It was a manual for astrologers. It was translated in the 12th century by John of Seville. Kitāb taḥāwil sinī al-mawālīd ("Book of the revolutions of the years of nativities"). translated into Greek in 1000, and from that translation into Latin in the 13th century. Kitāb mawālīd al-rijāl wa-ʾl-nisāʾ ("Book of nativities of men and women"), which was widely circulated in the Islamic world.[1] ʻAbd al-Ḥasan Iṣfāhānī copied excerpts into the 14th century illustrated manuscript the Kitab al-Bulhan (ca.1390).[15][n 1]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Ma'shar_al-Balkhi

"Abu Ma’Shar (full name Abū Maʿshar Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Balkhī أبو معشر جعفر بن محمد بن عمر البلخي) was a 9th century Persian Muslim astrologer whose books greatly influenced the development of astrology in Europe when they were translated in the Latin in the 12th century.

Ben Dykes in his translation of Abu Ma’shar’s On the Revolutions of the Years of Nativities cites David Pingree’s hypothesis that Ma’shar used his own natal chart in his writings. Based on this suppositon, Pingree estimated Ma’Shar’s birth data to be about 10 PM on 10 August 787 (OS) in Balkh, Khurasan (now Afganistan). On page 134 of Dyke’s translation he provides his version of Ma’Shar’s birth chart.

According to the Arabic text, notes Dykes, this natal chart is for a person born in a city with a latitude of 36N. Using this latitude and the data given, I reconstructed the chart as follows. I assumed that Abu Ma’Shar would be fairly certain of the position of his own Ascendant at latitude 36 North and that of his natal Sun, which is the easiest to measure because of the sun’s fairly constant rate of motion from day to day. The other planetary positions might vary from modern values due to differences in tables and methods of observation.

Because Ma’Shar was writing in the 9th century, the start of the tropical zodiac had shifted backward from Hellenistic times, as measured against the fixed stars, so I adjusted the ayanasma of the zodiac to calculate a chart which kept the following positions constant: Latitude of 36 North, Ascendant at 2 Taurus 54, and Sun at 15 Leo 57. (Dykes noted that he changed the original 15 Leo 57 in Ma’Shar’s text to 25 Leo 57 to match the value calculated by modern methods. I believe he should have adjusted the ayanasma rather than the position of the sun.) Given these conditions, the resulting birth chart for Abu Ma’Shar is the following...."

Above is courtesy of Anthony Lewis & birth chart calculations/data is courtesy of Benjamin Dykes, please note however, chart here is in gregorian tropical system: https://tonylouis.wordpress.com/2018/08/21/the-birth-chart-of-abu-mashar/

Raw Data

Horoscope Data

Comments

Natal Data

0787-08-14 22:05:00 LMT

36° 45′ 18.2″ N 66° 53′ 51.1″ E

Balkh, Afghanistan